We Should Be Measuring Well-Being Catalysis, Not (trying and largely failing to measure) Economic Productivity

Measuring Economic Productivity Is Pretty Much Bullshit -- We Should Be Measuring Well-Being Catalysis Instead

Periodically over the last decade (at least) I see media articles -- including some by actual serious economists -- hand-wringing about the supposed decline in workforce productivity in the last decades... (here is one random recent example, a search engine will find you many many. more.)

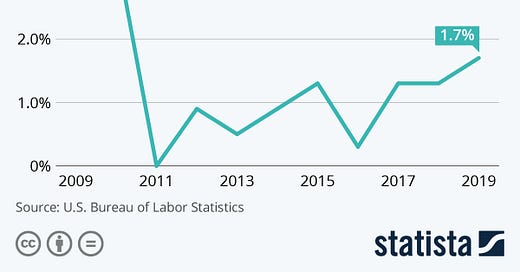

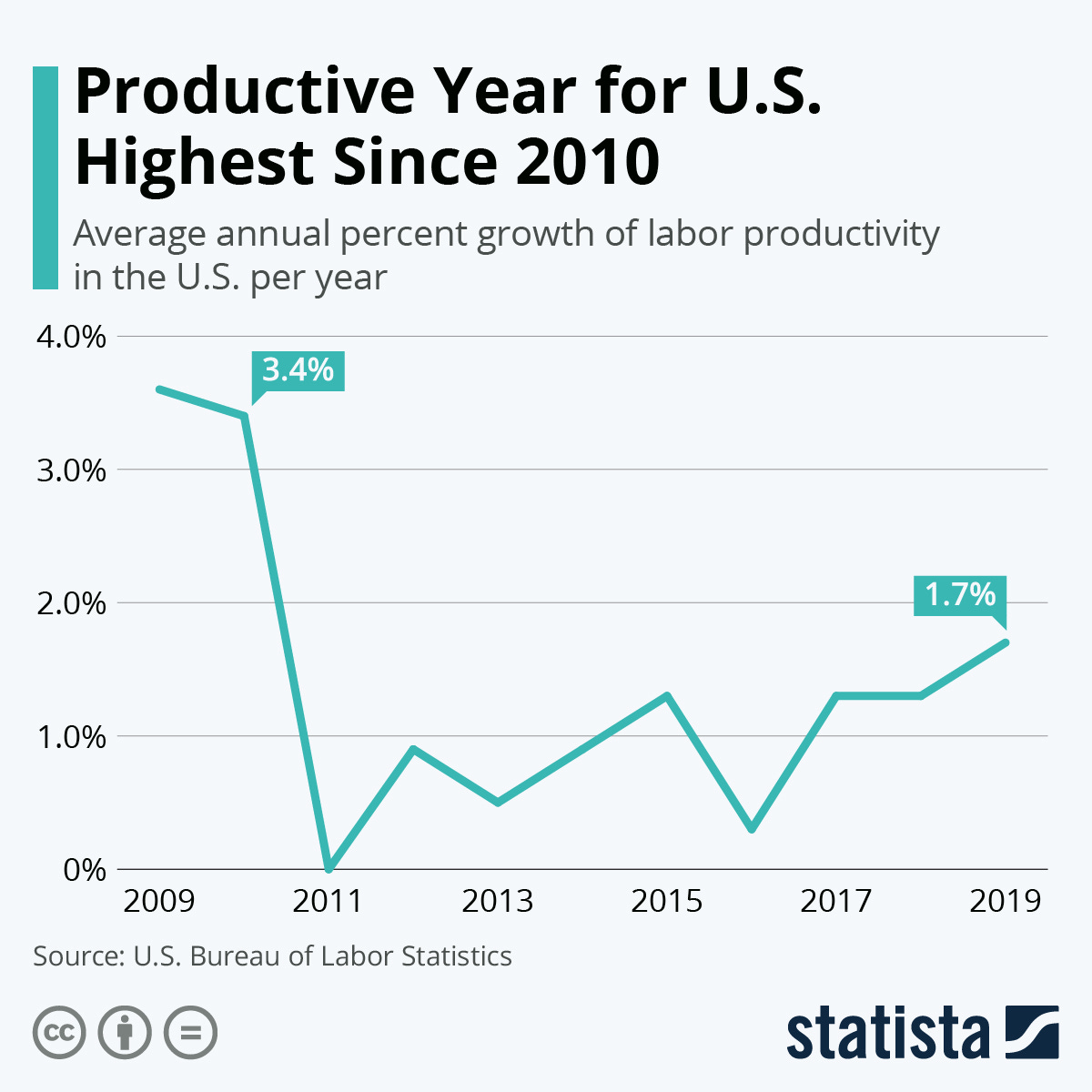

Fancy charts like this one from Statista

make it look like some definite, very meaningfully defined, real thing is being measured,

The lack of exponential increase in labor productivity is sometimes used as an argument that tech innovation has slowed down in recent decades — that the big innovations like electric power and the car are behind us and more recent inventions have been more minor in impact — that the narrative of accelerating progress toward Singularity is bogus in terms of the real-world economy.

It's always been clear to me this whole economic-productivity thing is mostly rubbish; now I'm finally taking a few moments to write down why I think that.

My key points in sum are:

The way economic productivity is measured is not very meaningful, for pretty plain-vanilla reasons related to the way tech advances lead to rapid changes in product and service features across so many areas, and the role of business strategy and marketing and general market conditions in corporate financial metrics

It would be a lot more useful to measure how well the economy and its various sectors catalyze emergence of human well-being. This is not extremely easy to measure but it can be done in a way that's far less fudgy than current standard attempts to measure economic productivity.

Economic Productivity Measurement is Largely Voodoo

How is economic productivity calculated? Roughly speaking, to calculate "labor productivity" one looks at stuff like

how many human-hours does it take to produce a certain unit of product?

There are also more general notions like "multifactor productivity", i.e.

how much of other inputs besides human-hours (physical equipment, invention, education, etc.) does it take to produce a certain unit of product?

I'll focus mostly here on labor productivity but the same basic points apply to multifactor.

"Product Units" Are Increasingly Volatile and Nebulous

First question: What is a "unit of product"

In some cases this may be very clear and simple, let's say e.g. a bathroom mirror. These have not changed too much over my lifetime, so it makes sense to compare e.g. how many human-hours of work (or how much cost in factory machinery and tools etc.) does it cost to make each bathroom mirror.

It's believable to me that the labor productivity in bathroom mirror production has remained around the same for the last couple decades. I know little about the bathroom mirror manufacture business, but I would imagine there was a boost in labor productivity (and multifactor productivity) in bathroom mirror production when the process shifted to being largely done by machines rather than people. Perhaps another boost when the factories got better automated with pervasive electronics. But I would suspect the factories for making bathroom mirrors are not yet fully robotized AI factories -- it's probably not yet cost-effective to refactor this sort of factory using cutting-edge AI powered robotics. So we're probably now in the interim between a bathroom-mirror-production productivity boost due to electronics-assisted factory manufacture, and the next productivity boost due to AI-powered robots-factories.

But let's look at some subtler examples of "product units" -- televisions, or mobile phones, or automobiles.

In this case we have a real problem in that the products being created today are radically different from the products being created a couple decades back. There is no direct way to answer how many labor hours or how much machinery it would take to produce a 1980-level TV or car using modern technology -- because this just isn't what's happening. --

One could try to dig a little deeper and look at product features... say, what is the amount of labor hours or machinery required to produce a particular feature like the ability to show a picture on a screen, or to make a car able to stop when a person pushes a pedal with their foot. But then how does one account for the fact that modern TVs give much clearer pictures than old ones, or the fact that modern braking systems have all sorts of fancy features that make them work much better than old-fashioned brakes?

Economists try to account for these changes by making "hedonic quality adjustments" -- so if it cost 60 human-minutes to produce a modern 2022 TV, one may count this as "90 minutes of making-1980-TV" because the 2022 TV is rated at 1.5x better than a 1980 TV.

But this is obviously largely a sort of “fudge factor” that is quite tricky to estimate accurately. One might want to ask: How much more human value does a high-definition TV give than a 1980 TV? How much more human value does a modern smartphone give than a 2000-era Nokia featurephone? But that is a sort of thing nobody tries very hard to estimate — instead the hedonic quality adjustment is made by looking at prices of old models versus new models at various time points, which is meaningful as far as it goes, but can be done in a variety of different ways for each product category, and depends on a great variety of cultural and market-structure factors.

But trying to go beyond hacky ways to estimate these corrections brings you down a path that is quite different from economics as conventionally understood -- i.e. trying to measure how much "fundamental value to the user" is obtained by various improvements in product/service features.

So, getting back to the broader picture regarding labor productivity and technological advance -- suppose that in the cases where the units of production have been very clear, like bathroom mirrors, it turns out that labor productivity has been stagnant or even decreased in recent decades? Would that tell us that it's also been decreasing in other areas like TVs, phones and cars? Not at all -- another possible interpretation of this would be that the benefits of advanced technology in recent decades have been more dramatically applicable to areas in which product-features have been evolving more dramatically. In fact this would make total sense, right? Newer industries are more likely to pervasively adopt new technologies, because they've had to build themselves more-so from the ground up in a world involving these technologies.

Another interesting example to think about is healthcare in the US. New therapies are being invented all the time which are hard to compare to older ones. But there are also some medical care aspects that have been fairly constant over time, like say the writing of a prescription for a throat infection, or the fixing of a broken leg with a cast (yes new antibiotics are coming out all the time, and casts are way better than when I was a kid, but these aspects are at least roughly the same as they were decades ago). It may well be that the number of human hours needed to provide a unit of basic medical care like fixing a broken leg or writing a prescription for a throat infection has increased in recent decades in the US, due to growing bureaucratic bloat in the medical business ... due to wasted human-hours filling out forms and dealing with related bullshit.

A friend of mine recently felt dizzy and went to a US urgent care facility for blood tests. They were inconclusive and so he was sent to the nearby emergency room, which proceeded to do the same blood tests over again, because they were not able to access the urgent care facility's test results in their computer system. This was just plain wasted work, caused by modern technology being deployed in a stupid and inefficient way. This sort of thing suggests that in at least some aspects, labor productivity may actually have decreased in medicine in the US in recent decades. Which is for very clear reasons -- not that technology to improve productivity has not been invented, but that it has been rolled out idiotically due to the intersection of regulatory and industry structure factors.

And we haven't even gotten to the hard stuff yet. What is the "product unit" for Facebook versus Twitter? Is it just a website or app, to be measured in terms of number of hours of engagement? Do we want to buy into the notion that a social-network company is more productive in some useful sense, if each labor-hour of its employees leads to more hours staring at the company's sites or apps? Apart from the questionable fundamental human value of staring at these sites, it's clear that these metrics depend very heavily on hard-to-pin-down cultural dynamics and word-of-mouth marketing and so forth...

Overall, it's pretty clear that in the modern economy, measuring output in terms of "product units" is very often Voodoo. In some cases it can be done simply, like how many bathroom mirrors of a given side are produced. But in the cases of medical care, cars, TVs or phones, where the product itself is ever changing and evolving, there is no simple way to quantify product … and no simple way to make accurate “hedonic corrections” across evolving product lines either.

Can't We Just Bypass Products and Measure Money?

One might say: Instead of trying to quantify product units, let's keep things simple and just look at the amount of money made by the company employing the people putting in the labor.

But this gets weird fast too.

One small issue is that it basically kills the ability to compare productivity across job categories. For instance, if we use money to measure output then Apple's labor productivity is much higher than that of a typical Android phone-maker ... not because Apple's phones are better devices (Apple and Android phones are about the same these days) or more efficiently made, but rather because their market positioning and product design have been clever enabling them to achieve a higher profit margin. In this case the productivity of Apple's factory workers will be rated as uncommonly high, even if in fact they are equally productive as a random Android phone maker's workers. The situation is rather that the productivity of Apple's design, marketing and business strategy teams is remarkably high. But separating the productivity of these different teams inside Apple out from each other is tricky and only possible if one can solve the "define the product unit" problem.

There are much bigger issues than this with using money to measure output, though.

There is no simple money measure to use that works across industries and company stages. For some companies at some stages, gross revenue is the right thing to look at, for others it's profit. Some businesses are run to maximize cash flow. Some businesses intentionally burn money in order to gain customers, views on their webpages, and so forth.

Further, the amount of revenue, profit or cashflow made by a given company in a given quarter or year depends a lot on overall market conditions. It feels a bit strange to say that workers in a given industry are less productive if profit margins decrease in that industry. This has some meaning, but it certainly isn't useful if one is trying to measure the extent to which new technologies have impacted productivity.

Perhaps rollout of new technologies in some industries has correlated with dynamics that decrease profit margins -- in fact this is clearly the case in very many verticals, where advanced tech has been used to reduce reliance on middlemen. In this case, profit margins for many industry players will decrease as new tech rolls out, meaning that even if technology is in some conceptual sense allowing units of product/service (which are hard to quantify and measure) to get produced more efficiently, productivity will still look like it's decreasing because quantitative financial output is decreasing.

In Some Cases Measuring Productivity is Meaningful and Interesting -- But These Cases are Decreasing

I don’t think classical measurement of labor and multi-factor productivity is actually useless — it may be valuable in specific cases where: A certain "product unit", with a fairly stable and well-defined set of features, has been produced steadily over a number of years. In a case like this one can look at the number of labor-hours, or the amount of machinery etc., needed to create each product unit.

Bathroom mirrors, forks and socks etc. are one sort of example, but one could also carve out examples like this in the domain of phones or TVs or other more tech-y sorts of products. The flagship phone from 4 years ago may have similar specs to the low-end phone from this year, so then one would want to compare the amount of labor-hours and machinery needed to produce a low-end phone this year with that needed to produce a high-end phone 4 years ago.

Doing this sort of calculation systematically and carefully would tell you whether productivity has actually increased, decreased or what for those segments of the economy that are fairly stable in terms of what they produce (i.e. for product categories where hacky hedonic corrections don’t play a big factor, nor new products that just didn’t exist before)

However, as Singularity approaches, what we’re going to find is that producing new stuff that didn't exist historically comprises a greater and greater portion of the economy. For this part of our economic production, I seriously don't see any non-fudgy way to estimate changes in productivity over time.

Why Not Measure Catalysis of Well-Being Instead?

Given all the complexities and hassles involved in measuring economic productivity beyond a diminishing set of cases where product unit definitions have remained fairly constant over time, one might wonder whether it's really a worthwhile thing to be doing.

The "hedonic corrections" used to figure out how much more valuable a modern high-def TV is than an 1980 TV or a 1970 black and white TV, may actually point the way toward something more interesting to measure.

Rather than making up a questionably-derived fudge-factor to estimate how much more "hedonically valuable" or "fundamentally valuable" a new TV is than an old one, what if we took this notion of hedonic value more seriously? This could let us measure economic productivity more meaningfully, and also have some more interesting uses as well.

How might we do this? Psychology, data, statistics and a bit of machine learning can be our friends here.

My friend Jeffery Martin faced a problem of measuring the degree of "well being" experienced by various people. He wanted to measure whether his Finders Course consciousness-expansion program was actually helping people improve their lives. What he came up with was a battery of already-existing psychological measures, such as:

Authentic Happiness Inventory

Center for Epidemiology Studies-Depression Scale

PERMA Profiler Questionnaire (Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment

Satisfaction with Life Scale

Gratitude Questionnaire

Fordyce Emotions Questionnaire

Meaning in Life Questionnaire

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Perceived Stress Scale

(In his study Jeffery also measured a Mysticism Scale and Perceived Nondual Embodiment Thematic Inventory, which measure "spiritual" state rather than generic well-being, but these are less relevant to the topic of the current blog post, though also certainly interesting to measure.)

Each of these survey instruments has its own issues and complexities, and each also has a body of serious research literature behind it. The point is not that these measures give us a perfect way to measure human well-being, but rather that they give us a decent stab at it, which is definitely worth taking.

So — suppose we give this sort of combined well-being survey to a random sample of people, and also measure what products and services they've used and purchased. From this dataset, we could make reasonable statistical inferences about the amount of well-being increase or decrease associated with a certain product or service among a certain class of people.

One could then estimate the well-being impact of a given company's products/services in a given quarter or year, and make an estimate of the "well-being productivity" of a company in terms of the amount of well-being impact it generates per labor hour (or other factor). Except I prefer the term "well-being catalysis" because it feels slightly wrong to say a product or service *produces* well-being ... it feels more right to say it catalyzes the evolution of the individual in a direction of greater well-being (or devolution toward lesser well-being).

One could use this sort of well-being-estimate to come up with more meaningfully humanly grounded "hedonic correction" numbers to estimate the human value of a high-def TV versus an old TV. But in the end this only solves a fraction of the problem with the typical notion of labor productivity -- it doesn't help with measuring the productivity of employees of Facebook or Spotify, for example.

Given the nature of the modern economy, what makes most sense is to give up on old notions of economic productivity, except in particular legacy sectors, and focus instead of understanding the impact of various activities on human well-being.

Doing this sort of systematic measurement would, however, expose a lot of issues more important than the ups and downs of economic growth and efficiency. It would expose the fact that a lot of what goes on in the modern economy actually decreases human well-being.

And this could lead to a different direction for economic policy than what’s currently dominant in most major nations. What if the government were to direct a certain percentage of collective resources specifically toward products and services found to increase well-being, and away from those found to decrease well-being? A pure libertarian philosophy would view this as overly paternalistic and intrusive, but the same "democratic socialist lite" philosophy that we have in modern democracies — the philosophy that has led us to public education, public libraries, national parks, carbon credits and (in every developed country but the US) robust public health care —would naturally lead to this sort of policy initiative.

Hi, Ben,

In general, I like this post. Note (of course) that the manufacturing sector (which these productivity metrics were designed for) is a small and decreasing part of the economy.

Please consider the service economy, and particularly the "care" industries such as child care and elder care (plus many others). These are "high human touch" lines of work. AI and other automation can help out around the fringes, like keeping records and doing paperwork, but the core of the job is direct contact between human beings.

I suggest starting with child care and elder care, because these face a critical dilemma (tri-lemma?). (1) Child care should be done with small numbers of children per well-qualified care-giver. (2) That care-giver should receive an adequate salary and benefits, commensurate with their qualifications. (3) The cost of providing this care should be affordable to parents of young children. These three constraints cannot be satisfied by a child-care company intended to make a profit. Typically, one, two, or all three of these constraints are egregiously violated. Child care (and increasingly, elder care, which faces similar constraints) is a critical part of our economy.

Technological advancement helps, in the sense of creating more wealth for the society, but some of that wealth must go to subsidizing child care. We are capable of creating a society that provides excellent child care, but we must have the will to pay for it. (I would claim that if we want to create a good society, it *must* include excellent child and elder care. So figuring this out is an imperative.) And the metrics you criticize are worse than useless in guiding this process.

I offer this as an argument for strengthening your criticism.

Cheers,

Ben Kuipers

Omg, how complex to come up with measurements. It's daunting even to read this. What strikes me is how male this is, bogged down in objectivity. So I'm asking myself what female would be. I'm reminded of Bucky Fuller being glad he didn't get glasses early on. Not seeing the blackboard he didn't get bogged down in details which let him see the bigger picture. What's a bypass to measuring that we more easily could deliver to the world? Like getting right to making that shift from materialism to caring to occur and not just rationalizing about it. How to do that? A good topic, I'd think.